The armbar is a fundamental submission that ties in perfectly with the triangle choke, with both attacks often being used in conjunction with one another. The beauty of an armbar comes from both it’s simplicity and it’s endless complications, there being plenty of grip-breaking techniques from the Spiderweb position, variations depending on the angle of the arm or the position of the opponent, and counters to every escape imaginable. The original pioneer of Women’s MMA in the UFC, Ronda Rousey, made her entire career both as a Judo Olympian and as a UFC World Champion off the back off this submission only. Her career highlights make a lovely example of just how much mileage a great grappler can get out of the armbar all by itself:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GAYqw70QD3A

Before Rousey ever even set foot on the Olympic mats, there was another MMA competitor who was known as a master of the armbar. Antonio Rodrigo “Minotauro” Noguiera had already put together 10 wins via this particular submission before he entered the UFC in 2007, all during the very best years of PRIDE FC and RINGS. The armbar was already a mainstay of MMA and BJJ competition at this point, first appearing in sanctioned MMA in Japan, at Pancrase 1 in 1993 when Takaku Fuke defeated Vernon White in both men’s first MMA fight out of 51 and 61 respectively. It wasn’t long before it appeared in the USA at UFC 2 when Royce Gracie submitted the experienced (for the time) grappler, Jason DeLucia.

The armbar was a long-time favorite submission of several members of the Gracie family in fact. Helio Gracie has three recorded victories via armbar dating from 1937 against Erwin Klausner to his first recorded match in 1932 against a boxer, Antonio Portugal. In Reila Gracie’s Biography of her father, “Carlos Gracie: O Criador De Uma Dinastia“, she mentions Carlos as winning several fights via armbar back when there was only a handful of people in Brazil training in what we now call BJJ under Mitsuyo Maeda. Maeda studied directly under the creator of Judo and the founder of the Kodokan Institude, Jigoro Kano from his arrival there in 1895 until he left for America in 1904, eventually reaching Brazil in 1914 and starting to teach Carlos in 1917. This is where the armbar came to BJJ, at the very start of it’s separation from Judo when it was still known as the Juji-Gatame.

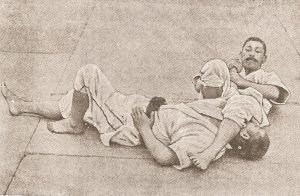

The Kodokan Institute’s popularity and success came from the very same thing that propelled the Gracie family to fame and fortune, the willingness to arrange challenge matches and the skill to win most of them. It was one particular series of challenge matches that piqued Kano’s interest more than most, those between the Kodokan Institute and the Fusen-Ryu school in 1900, while Maeda was still at the Kodokan. This school was dedicated to preserving the groundfighting aspect of Jujutsu and the master of the Fusen-Ryu school at the time was Mataemon Tanabe, pictured below demonstrating an armbar.

Tanabe was so impressive in his victories throughout many challenge matches in fact, that Kano himself convinced him to help the Kodokan Institute with their Ne Waza (groundwork), starting the trend towards a focus on submissions. Tanabe was a fierce competitor who had been teaching since he was 17 and beating grown men since he was 14 thanks to his father’s influence. Not much is known about his father Torajiro, other than he was the head of the Fusen-Ryu school prior to passing it on to Mataemon, and he also favored ground work over throws which was highly unusual for the time.

Whether Mataemon Tanabe, his father Torajiro, or even the man who founded the Fusen-Ryu school in the early 1800s, Motsugai Takeda, were individually responsible for the creation of the armbar is unknown. None of them have ever been credited with it’s invention and Mataemon being renowned for his groundwork in general points to the armbar being just one of many attacks that he was proficient in, as opposed to something revolutionary he had brought to the art. While the traditional Juji-Gatame position of the opponent’s arm being between the attacker’s legs with one over the head and one over the chest or into the armpit can’t be traced back beyond Jujutsu, the concept of the armbar certainly can.

Above is a Cambodian stone carving that depicts the 8th century art of Khmer Wrestling, one of many that shows the early evolution of submissions. The configuration of the attacker’s arms around his opponent’s one arm appears to be applying outward pressure against the elbow, very similar to what we now call a straight armbar in BJJ. It’s unclear whether or not this would have been used as a submission, or perhaps to force the opponent to the ground, although the latter seems more reasonable given the body positioning.

The armbar as we know it now might be anywhere upto 200 years old or more, but the principle of creating a fulcrum with your own body and using it to hyper-extend your opponent’s elbow beyond breaking point is as old as grappling itself.

This piece is part of a series diving deep into the history of various submissions, click here to look through the rest of the series.